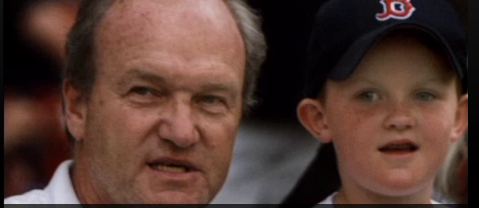

With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

In his latest column for The Daily Beast, Mike Barnicle juxtaposes the lives and death sentences of Pfc. John Hart, 20, killed outside Baghdad, and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the now convicted and sentenced Boston Marathon bomber. Unfortunately, it will be Tsarnaev’s name in the news over the next few years, when our focus should be on remembering and honoring Pfc. Hart, his life, and his service.

Read his column here.

https://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2015/05/17/dzhokhar-tsarnaev-a-death-deserved.html

Mike joined ESPN Radio’s The Sporting Life to reflect upon the one-year anniversary of the Boston Marathon bombings. “There are going to be a lot of poignant moments at the conclusion of this year’s Marathon. Obviously many people will be thinking about those who died…but more specifically [about] the youngest…of the victims. Martin Richard, eight years of age…died simply because his family decided to have a fun day at the Marathon.”

This is WEEKEND EDITION from NPR News. I’m Scott Simon. Boston Strong has become an American phrase over the past year after bombs exploded at the finish line of last year’s Boston Marathon. Three people were killed – Krystle Marie Campbell, who was 29, Lu Lingzi, a graduate student from China, and Martin William Richard, an 8-year-old boy. At least 264 people were injured, many of them losing legs and arms. Sean Collier, an MIT police officer, was also killed before police caught up with two brothers, Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, in nearby Watertown.

Tamerlan was killed in a firefight with police. Dzhokhar Tsarnaev escaped, but he was captured later and will stand trial in November. The federal government has asked for the death penalty. Boston Strong has described the grit and grace with which Boston and the people injured have lived through their losses. We want to turn now, as we did last year, to Mike Barnicle, the definitive Boston columnist. He’s also a frequent contributor to national publications and a fixture on MSNBC. He joins us from our station WGBH in Boston. Mike, thanks for being with us.

MIKE BARNICLE: I’m happy to be here, Scott.

SIMON: Can you see ways, large and small, in which the city has been changed?

BARNICLE: Yeah, you can. It helped establish a firmer bond of community, I think. And the marathon, basically, is a 26-mile-long block party in greater Boston. It’s a community event much more than it is a sporting event. So what happened in the marathon last year, I think the ensemble cast of all of those who participate, all of those who witness it feel stronger about themselves, feel more pride in the event and more hopeful about the future because of what they endured, what the city endured and what the city bounced back from.

SIMON: I think we all remember the weeks and months that followed and some of the scenes that unfolded. You think of Neil Diamond turning up to sing “Sweet Caroline” at Fenway and bombing survivors getting cheered at Bruins’ and Celtics’ games. Were some gestures better than others?

BARNICLE: You know, there’s a certain bittersweet aspect to this year’s marathon in terms of what people remember and what happened and what has happened to the survivors across the year. Young Jane Richard, Martin Richard’s sister, she is now 8 years of age. She lost her leg last year while her brother lost his life. She was on the field at opening day a week ago Friday. But you could see on the faces of the professional baseball players how struck they were by her courage.

You can see it on the face of Jeff Bauman who lost his leg. His fiancee, Erin Hurley, was running the marathon last year. He was there to witness her cross the finish line, lost his leg, nearly died. They’re expecting a child in July. But they are all hopeful signs, larger symbols of a city that bounced back and stays bounced back.

SIMON: Mike, you’re in the news business. But at this point, it seems you have your pick of things to comment on or not. Are you going to pay close attention to the trial?

BARNICLE: Not really. The trial really doesn’t interest me much at all. I think I pay more attention to the daily occurrences in and around the approach of this year’s marathon. One of the things that stands out in my mind’s eye is there is a fire station on Boylston Street in Back Bay in Boston 300 yards from the finish line. And last year, a young firefighter, Michael Kennedy, ran from that firehouse down to the marathon finish line as soon as the explosions occurred without worrying about his own life or limb.

And he died in a fire in Back Bay, four blocks from the finish line, a few weeks ago. So I think a lot of people will be thinking about him and about the occurrences since the marathon a year ago. This city endures, prospers, survives and is standing up every day.

SIMON: Mike Barnicle in Boston. Thanks so much.

BARNICLE: Thank you. Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

https://news.wsiu.org/post/year-after-bombings-barnicles-boston-stronger-ever

By Jason Mastrodonato / MLB.com

BOSTON — Brothers Colin and Nick Barnicle have long been in the field of video production, where they’ve found plenty of success and gratification, including “Down the Line,” a behind-the-scenes documentary on Boston’s Fenway Park released in 2011.

So when the tragic bombings took place on Marathon Monday, the Belmont Hill graduates knew they had to get back to Boston.

“Usually, we would go in and pitch an idea,” said Colin Barnicle. “We said, ‘Let’s just do this, because we want to do it and help out in the way we know how.’ And the way we know how is to put our work into a video.”

The Barnicles, along with friend Jeff Siegel, traveled from New York to film and edit their own One Boston video in less than 48 hours. They drove to Boston on Saturday, set up two cameras in Fenway Park and captured the emotion of the day baseball returned to Boston.

The one-minute, 50-second video has no footage of the bombing, instead focusing on the recovery process afterward.

“We just took our cameras and equipment and said ‘Let’s see what we can get out of this,'” Colin Barnicle said. “It was really just 35,000 people and thousands more outside the stadium just taking that cathartic breath, that sigh, that ‘This is over let’s get back to normal.’

“This was something we could tangibly see, feel and experience together.”

With the voice of Mayor Thomas Menino playing in the background, the up-close style gives the video a personal touch that the Barnicles hope people from cities all across the country will feel.

It might be their most satisfying project to date.

“It was the first time in a long time, since 2004, where the team and the fans connected on a totally different level,” Colin Barnicle said, describing the scene from Fenway on Saturday. “Look at the [David Ortiz] speech: The players were feeling along with the fans.”

Contributions can be made at OneFundBoston.org.

https://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20130421&content_id=45455236&vkey=news_mlb&c_id=mlb

MIKE SHARES MEMORIES OF FENWAY PARK

Thu Apr 19, 2012 2:50 PM EDT

Evelyn C. Savage

Our man Mike Barnicle has talked a lot and written a lot about Fenway Park over the years. Lately, he’s been talking a lot about the park’s 100-year-anniversary, which will be celebrated Friday, April 20th with a game against the Yankees that begins at 3:05 p.m. (the time the Sox began their game against the New York Highlanders). Hearing Barnicle discuss his first visit to the park in the mid-1950s is hearing his rite of passage story. It seems safe to say he views Fenway as his second home, if not maybe his first home.

I spoke with Barnicle this Wednesday about the big anniversary, his relationship with the park, why he doesn’t heckle the team during a game, if there’s any rival to Fenway, and whether it was his father or his mother that was the big baseball fan in his family.

Morning Joe: Why does Fenway hold such a special place in the hearts of not just Bostoners, but seemingly all New Englanders?

Mike Barnicle: I think, in large part, it’s because of the permanence of the facility itself. When you consider the fact that we live in a time now where people move almost relentlessly. Very few people live in the same house they move into when they’re married or the same neighborhood when they’re married. Very few people certainly live in the neighborhood they grew up in. We change all sorts of things in rapid time. We sit here in front of TV sets with clickers in our hands, and change channels. We change spouses and partners; divorces are epidemic considering to what the divorce rate was 30 or 40 years ago. All of these things that we’re used to today, these elements of change that are around us, to some people and maybe to most people at some level within them, can be kind of disconcerting. Like ‘Jeez, that place used to be a drug store when I grew up.’

MJ: And now it’s a parking lot.

Barnicle: Now it’s a parking lot or a high rise or a McDonald’s or whatever. And then you get to Fenway Park. And it is the same today in large measure as it was the first day you walked into that park when you were seven years of age holding your father’s hand. And there’s a sense of permanence to the ball park that gives people, I think, a feeling of security or a sense of sameness to the area; that gives a lot of people a sense of happiness. It’s still the same today coming up out of the subway stop at Kenmore Square. Walking through the square, up across the bridge on Brookline Avenue to Lansdowne Street. The light stands. It’s the same. The bricks are the same. And I think in an age of constant change and great change, I think that brings a huge measure of relief to people.

MJ: And it’s something you hand down from generation to generation.

Barnicle: Yeah. As your father or grandfather, depending on your age, took you 40 years ago, 60 years ago, whatever, however old you are, 20 years ago, you can take your son or daughter to the game today and then hopefully 20 or 25 years from now, they can take your grandchildren to the game, and it will be the same.

MJ: I don’t know the reasons why it has stayed where it is and parks like Yankee Stadium or Shea Stadium have not. Can you give a general primer why Fenway Park hasn’t moved in a 100 years, given that it’s a very busy, bustling area now?

Barnicle: There are a couple of reasons why it has remained where it is and remained pretty much the way it has always looked. The biggest reason right now is after the sale of the team in 2001. The debt service to build a new ball park in another area of the city – say down by the waterfront – would have been too heavy for the present ownership group to carry. They didn’t want to carry the debt service, having just paid a record amount of money for the team and for the ball park. They didn’t want then to transfer the debt service that they were already carrying to the increased debt service of construction for a new ball park. That’s one reason. That’s a financial reason, obviously.

But there’s another reason, and it is this: That one of the members of the ownership group, Larry Lucchino, who came in in December 2001, was the guy who built Camden Yards in Baltimore. And built it in the early ‘90s; I think it opened 20 years ago. It’s been open since 1992. Built it with an idea that a ball park around Camden Yards – the old railroad yards in Baltimore – would create, he hoped, the establishment of a brand new urban neighborhood, which it did. And the refurbishing and rebuilding of Fenway Park since 2001 has created a new urban neighborhood in Boston. It is now a very hot neighborhood and is continuing to grow hotter and will only increase in attractiveness to both residents and businesses. Because the ball park is a magnet. It is the single largest tourist attraction in Boston now and it’s not just a six or seven-month-a-year facility. It’s open all year round. You can have a wedding at Fenway Park.

MJ: Have you been to a wedding there?

Barnicle: I have. I’ve been to bar mitzvahs at Fenway. It’s created a thriving, fairly young and affluent neighborhood around the ball park, which is something that did not exist prior to rebuilding the place.

MJ: And it is centrally located in the city.

Barnicle: That’s part of the magic of the park as well. If you’re there for just a few days in Boston, you can walk to the park. You can be staying around Boston Common; you could be staying with friends in Jamaica Plain. It’s easy to get there. It’s not exactly great to park around there, but what ball park is great to park around? You can get there fairly easily.

MJ: It seems safe to say you’ve done this many, many times in your life, but I have to ask about your memories of your first time at the park. And where did you sit in the park as a child? And where do you sit now?

Barnicle: The first time I went to Fenway Park was probably 1950. It was the early ‘50s, and it was my father taking me to the game. And what I have full retention of is of the electric sight of coming up the ramp on the first-base side (and it’s still the same sight today), and you come up into the splendor of green that you see in front of you. The lawn, the wall, the sun sparkling on both. And when you come up the same ramp today for a day game or night game, it’s still shockingly beautiful. At least it is to me. The ball park itself…where did I sit? We used to sit when I was a kid – tickets were obviously cheaper then – we’d sit in the Grandstand section. Maybe section 15 or 16, which is along the right field foul line.

But you know, things change. You go to work; you get lucky; you do well; you make a little money. Some people buy beachfront property. I buy season tickets. So, I have and have had for quite some time, ten season tickets in various locations around the ball park, all pretty good seats. The seats I sit in are right by the Red Sox dugout. And I’ve sat there for years.

MJ: Where you proceed to heckle the team all season?

Barnicle: You know what, not only do I NOT heckle the team, because I have an appreciation for how difficult that game is to play. But if you would watch me during a game — and please don’t — I only rarely show any emotion at all. Like standing up or cheering or clapping. I like to just watch the game. And I do not enjoy taking people to the game who want to talk about anything other than baseball and who don’t get the fact that, you know, ‘Hey, I’m trying to watch the game. You want to talk about what’s going on in the game, feel free. But don’t be talking to me about your hedge fund.’ But that would be very unlikely for me bringing a hedge fund guy to sit with. But you get the point.

MJ: So there’s a hierarchy of mental involvement when it comes to watching the game, and you like to focus is basically what you’re saying.

Barnicle: Yes.

MJ: If you’re going to Fenway for the first time, what are the rules of going to a game?

Barnicle: You should enjoy where you are, first of all. Because there’s not a facility like it in the country for baseball.

MJ: What do you mean by that?

Barnicle: The field is quirky in its arrangement. It’s not like a cookie cutter field. It’s not like 325 down the line at left, shoots out to 345 at left center, 410 in center, 345 in right center, 325 down the line at right. It was designed at an earlier, easier time. You’ve got the famous wall, and they post it at 310, but it’s probably about 300 feet from home plate. Not a big distance for a major league hitter. The wall was put up to prevent mud slides, really. The park was built on a landfill. There’s a crazy, cookie-cutter design to center field. There’s a corner of the bull pen that makes it one of the deepest center fields in the major leagues. It’s got a wide, horseshoe-shaped right field that if the right fielder misses the ball on the bounce, the ball can carom like a pinball all the way around. You can get yourself an inside-the-park home run. It’s interesting. And it’s different from most parks.

MJ: Is it safe to say Fenway is your favorite park? Is there a rival in your mind?

Barnicle: Wrigley Field [in Chicago] is pretty nice. Almost as old. Where the Cubs play with the vines on the wall on left field. And it’s in a great neighborhood, as well. Like with Fenway, it’s a magnet for a younger crowd. That’s a nice ball park. Some of the newer ball parks are really nice. The ball park in Pittsburgh is a spectacular ball park. Again, it’s right downtown. The Denver ball park, built in the LoDo area, completely brought back that neighborhood. San Francisco has a fabulous ball park. It’s right down in the Embarcadero. You can walk there from downtown San Francisco.

And there’s a difference, too. If you want to play baseball, you want to play in a park and not a stadium. It’s nothing but rhetorical, but a stadium symbolizes something larger. You’re going to play football in a stadium. A park connotes someplace you come, it’s smaller and more comfortable.

MJ: What do you remember about the team when you first went to a game?

Barnicle: I can remember many specific players. Jimmy Piersall, Number 37. Sammy White, the catcher, Number 22. Ted Williams, Number 9. Harry Agganis, Number 6, died of pneumonia in Santa Maria hospital in Cambridge after a road trip in 1955. I can remember all of that. I can’t remember what I had for breakfast this morning, but I can remember that.

They were a dreadful team then. Always finished in fourth place. There was an A-team American League division then. There were only 16 major-league teams. I could remember most of the teams. Most of the teams that played the Red Sox would stay in the Hotel Kenmore in Kenmore Square. You could camp out and get autographs because the players would just walk the 150 years to the ball park. Every team stayed there with the exception being the Yankees. They stayed at the old Statler Hilton in Park Square in Boston. I can remember vividly much of that period of time.

MJ: You mentioned your father taking you to your first game. What kind of a Red Sox fan was he when you were younger?

Barnicle: He was not a huge fan, turns out thinking back on it. He took me because I loved baseball.

MJ: So you asked him to take you?

Barnicle: Yeah. He liked baseball, but he was nowhere near the baseball fan that I was then and obviously became. He was like most people his age in that era. Newspapers cost two cents each, so we used to get six or seven newspapers a day in the house. And you’d follow almost everything through the newspaper, baseball included. My mother was a big baseball fan. She loved Ted Williams. She would sit on the front porch of our home, with the radio on and listen to the ball game.

MJ: Would she go to games with you when you were younger?

Barnicle: No. We didn’t have a lot of money. And it was a huge treat. And I assume, looking back on it, that a few economic tricks took place for us to be able to go to a ball game.

MJ: When you were younger, how many games would you be able to see in a season?

Barnicle: I didn’t go to that many when I was that young. But I was also lucky in that my uncle played major league baseball for the then-Boston Braves (now the Atlanta Braves), and he was a pitcher for the Boston Braves. And so growing up, my cousins and I had an entrée into that world that very few kids did. By the time I was 12 or 13, and given the ease of access to get to the games and the fact that they weren’t selling out, we went to a lot of games. And a lot of the guys that he played with, they were coaches on major league teams.

MJ: When did you start bringing your own kids to Fenway? Did you want them to be massive Sox fans at a young age?

Barnicle: Here’s the deal on that. I would take our two oldest boys to games from the time that they were five and six. And I would take them, first of all, because I was in charge of taking care of them on a particular day, so I’d take them to the ball park. And we would sit upstairs. And I never took them with the idea that I’m going to inculcate them. I don’t think you can do that. They are either going to like it or not like it, but I wasn’t going to force it on them. And luckily for me, they not only liked it, but loved it. They played it at a very high level throughout their young lives and still play it. They play hardball in a hardball league in the Bronx. One of them played a year of minor league baseball. They both played college baseball. And they do film stuff now, they have a production company for ESPN’s “Baseball Tonight.”

Sarah Glenn/Getty Images

Bobby Valentine needed a coffee.

It was five minutes to seven on a soft spring morning at JetBlue Park in Fort Myers, Florida, and the 61-year-old manager of the Boston Red Sox had just arrived in his office — a windowless room located on a long cinder-block corridor within a baseball facility built seemingly overnight in a state where high unemployment, low union clout, and Lee County official eagerness resulted in farmland being turned into a state-of-the-art ballyard in stunning speed.

“Forgot we had a night game,” he said. “I could have gotten here a little later if I remembered we were playing a night game today.”

“What time would you come then?” he was asked.

“8 a.m.,” he answered. “Kitchen’s not even open yet. I need a cup of coffee. One cup. That’s all I need in the morning. One cup to get me going.”

There was a coffeemaker on top of a hip-high steel file cabinet along the wall behind his desk. Valentine stood up, placed a coffee cartridge in the coffeemaker, and touched the “on” button with his index finger. Nothing happened.

“Jesus Christ,” he muttered. “Is this thing working?”

He pushed the “on” button again. And again, nothing. Then he moved the file cabinet away from the wall, removed the coffeemaker’s plug from the outlet, and put the plug into a second outlet. Still nothing.

“Goddammit,” he said. “That’s distressing.”

He hit the switch a third time and then hit the coffeemaker. Now he stood staring at it with the same look he’s given countless times to players who failed to hit a cutoff man or missed a bunt sign.

“I’ve got to get this thing working,” he said to himself. “Watch, I’ll get it working.”

“You sound like a know-it-all,” he was told.

“Hey,” he laughed. “That’s probably because I am a know-it-all.”

So, here he was, Bobby V, the pride of Stamford, Connecticut, greatest high school athlete in that state’s history, nine years out of the major league managerial loop, standing in his baseball underwear, cursing a coffeemaker, carrying all the baggage as well as optimism that has clung to him across a lifetime in the game.

“I’ve learned to not dwell on the last loss,” he pointed out. “I now prefer to think of the next win.”

This week he takes a team — the Boston Red Sox — into a season still in the shadow of a disastrous September collapse and a nightmarish offseason; the manager, Tito Francona, departed, followed by the general manager, Theo Epstein, amid a series of news stories that made the club appear more dysfunctional than the cast of Jersey Shore.

He has a permanent smile on his face and an iPad on his desk. There is a stack of unopened mail on a round table. There are several books next to the letters: People Smart by Tony Alessandra and Michael J. O’Connor, The Leader Within: Learning Enough About Yourself to Lead Others, by Drea Zigarmi and Ken Blanchard, and Thinking, Fast and Slow, by Daniel Kahneman.

“Kahneman,” Bobby Valentine notes. “He was awarded the Nobel Prize.”

So who is he in this, the spring of his 61st year, more than 40 of them spent in baseball? Is he, as a critic like Curt Schilling contends, an overmanaging control freak who eventually exhausts both players and the front office with constant tips on how to lay down a bunt, turn a double play, round third, load an equipment truck, make a sandwich, or select a wine? Or is he simply a guy whose high-wattage personality, eternal optimism, endless curiosity about multiple topics, love of the game, and substantial IQ and EQ (emotional intelligence) have him roaming across various facets of life as if each sunrise came with a buffet of big thoughts to be sampled or devoured? A guy who has managed to assemble all his experience into nuptials where instinct finally marries wisdom?

For years — before he was either banished, forgotten, or thought to be too electric to handle — Bobby Valentine played and managed games from eye level. And while he remains unafraid to grade his new club, his absence from the scene — as a true participant with a number on the back of his jersey — seems to have brought a caution about where his rhetoric might lead when conjecturing about the record and road ahead for the 2012 edition of the Red Sox.

Through the time in Texas and New York, he was a man of the moment. Always there with something to say about nearly everything and everyone; 162 games, 162 potential chances for combustion. But life in Japan and working for ESPN did something that probably surprised even him: It broadened his horizons, exposed him to different styles of management and leadership — and Valentine is a sponge for anything he thinks might give him an edge. He absorbed all of it and now takes those lessons to this job, this team, and a town that has been waiting in judgment since Evan Longoria’s home run landed in the left field stands last September, cementing a historic Red Sox collapse. And he is indeed ready to be judged, booed, cheered, second-guessed constantly, and have the F-word used as an adjective before his last name if the Olde Towne Team doesn’t come out of the gate playing .800 baseball.

“I understand expectation and I understand there’s only so much you can do about the perceptions others have about you,” he says. “Actually, there’s not much you can do. But I’m older now; I’m more interested now in building my character and not my reputation. That wasn’t always the case, though.

“I don’t really get concerned or caught up with what people think of me anymore. That’s reputation. I know that sounds like a line, but it’s a fact. I try to do what’s right as often as possible … that’s character.”

First time he got fired, he was about 15. He was working in a clothing store in Stamford called Frank Martin and Sons.

“I was selling clothes,” he recalls. “I guess I wasn’t very good at it, so I got fired. I was surprised, but I wasn’t crushed.

“I got fired in Texas. Got fired in New York. I survived. Got through it. It’s all part of life’s lessons, and I’m still learning. Hopefully, every day.”

Now he finds himself back at work, back in uniform, in a market that can often feel claustrophobic. Since 2004, when the Red Sox beat the Yankees in an earth-shaking, universe-altering, come-from-behind playoff series for the ages and then, seemingly as an afterthought, won the World Series, too, “The Nation” greets each season with high expectations and low patience. Valentine was hired during a winter of chicken-and-beer tales, and each new story and every day only seemed to add to the clamor and anger that came with the collapse.

“I don’t think I was hired to change the culture of the team,” he says. “I don’t think there is a culture that needs to be changed. I see a group of players, very good players, who know how to play the game and play it very well.

“Now, the culture of the game itself,” he continues, “well, I do think there can be some changes, some adjustments if you will, that I’d like to help happen. Maybe a little reversion to Baseball 101.

“Here’s what I mean: I’ve noticed that across the last five or 10 years in the game there seems to be a growing tendency to wait for the home run. And I think that’s dulled the senses a little bit, the baseball senses. And I don’t think that waiting for the home run to occur is fulfilling enough for a baseball player.

“Baseball players know instinctively that there is much more to this game. I walk around the locker room and I see Adrian Gonzalez and Dustin Pedroia and Jacoby Ellsbury sitting around talking with Dave Magadan, talking about baseball, talking about all the little things that make up the game, the things that help a team win, things other than the home run, and it makes me happy. They get it.”

And Valentine got it, too, got the one thing he thought he might never get again: the chance to manage another major league team, to measure his day by innings instead of by wristwatch, to think of what he might want to do in the top of the eighth during the bottom of the third, to live and breathe every moment from eye level in a dugout instead of off a TV monitor in the press box, to again be the real Bobby V rather than Bobby Valentine, analyst on Baseball Tonight, former manager of this club or that one.

He is semi-fluent in Japanese. He is a gourmet cook, a ballroom dancer, inventor of the wrap sandwich, a consumer of Malcolm Gladwell’s books as well as sheet after sheet of sabermetrics; he has been fired by George W. Bush, worn a disguise in a dugout, colored his hair for TV, and never, not once, missed an opportunity to grab life with both hands each and every day.

He is Bobby Valentine, back in the game, back in the one place where he feels most at home, most comfortable: a dugout, with a lineup card in his grasp, a field in front of him, and a long season of hope and opportunity ahead with one objective, the single item that has driven him through the years.

“The win, baby,” Bobby Valentine said. “The win.”

BY MIKE BARNICLE

It was nearly dusk, the weak winter sun finally surrendering for the day, and Kevin White was leaning against the brass rail that stood in front of a wide glass wall as he looked at the view from the mayor’s office, down toward Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market. It was close to Christmas and people below walked through oatmeal-colored slush to shops that glittered in the approaching grey of late afternoon.

Look at it, “ Kevin White was saying then. “Look at all the people down there. Ten years ago the place looked like a stable. Now it’s a palace.”

A thief called time has stolen more than three decades since he stood at that window. And a vicious illness called Alzheimer’s robbed him of memory, slowly pick-pocketing what he knew and loved about his family, his friends, the substance of his days, his accomplishments, his election wins and losses, his pride in appearance and, finally, his life.

Remarkable urban fact and extraordinary political reality: Kevin White was one of only four mayors to govern Boston across the last 50 years. Half a century: Four men!

He arrived at the old city hall on School Street, having defeated Louise Day Hicks who knew where she stood on race and schools and busing in the fall of 1967 after a bruising campaign that held the outline of a fire that would nearly consume the town seven years later. He had been Massachusetts Secretary of State since 1960 and he was an odd element added to the tribal politics that then dominated Boston.

Kevin White was always more Ivy League than Park League. He felt more at home in Harvard Yard than he did at The Stockyard. He was Beacon Hill more than he was Mission Hill. He knew all about Brooks Brothers and not much at all about the Bulger Brothers. He read history rather than precinct returns. He was neither a glad-hander or a back-slapper and other than his wife, his family, a few close friends like Bob Crane, the former Treasurer, and a couple others involved in politics, he had a distance about him that kept him from succumbing to the two items that have proven to be a death sentence to so many others around Boston: Resentment and envy. White was a big-picture guy in the small-frame city of the mid-20th Century.

He enjoyed politics the way chronic moviegoers enjoy a good film: For the plot, the storyline and, most of all, the characters. His appreciation for the business of elections was borne in part through his father Joe who was on so many municipal payrolls when White was growing up that he had earned the nickname, “Snow White and The Seven Jobs.” And there was his father-in-law, “Mother” Galvin, who dominated politics in Charlestown and defined a mixed marriage as an Irish girl marrying an Italian.

The first time he met John F. Kennedy was on the tarmac at Logan Airport in October 1962 when the President of the United States came to speak at a Democratic State Committee dinner at the old Armory on Commonwealth Avenue, across from Braves Field, now all gone, replaced by gleaming new dorms and a Boston University athletic center.

White was running for re-election as Secretary of State. The statewide candidates were told they had a choice: They could meet the President at the airport or they could have their picture taken with him at the black-tie dinner that evening but they could not do both.

“When he came down the steps of Air Force One, it was like the Sun-King had arrived, “White once recalled. “And then when he said what he said to Eddie McLaughlin I realized how different he was from anyone I had ever met before.”

The late Edward McLaughlin was then Lt. Governor of Massachusetts and he was first in line to greet Kennedy. And, unlike White and the other statewide candidates there, he wore a tuxedo. He was going to get his picture taken twice.

“I will always remember the twinkle in Kennedy’s eye when he saw Eddie in the tux, “Kevin White remembered. “He touched Eddie’s lapel and said, “Eddie, taking the job kind of seriously aren’t you?’ God that was funny.”

Through four city-wide elections, two of them – in 1975 and 1979 – knock down, hand-to-hand combat with former State Senator Joe Timilty and the searing, bleeding open wound that was busing, White’s ambition for any higher office diminished and disappeared, replaced by a desire to grow the city from a place of narrow streets and even narrower vision into a wider arena where people would come, go to school and stay; where development would flourish and provide a new coat of paint for a tired relic of a town that had a death rattle to it in the early 1970’s; he wanted to put his little big town on a larger stage for the world to see.

Kevin White was unafraid of talent, a big asset in attracting those who turned ideas like Quincy Market, Little City Hall, Summerthing and Tall Ships into a reality that helped the city grow up rather than simply grow older. Downtown began to flourish at the same time different neighborhoods retreated into a type of municipal paranoia, a kind of virus that spread block by block, transmitted by a near-fatal mixture of political incompetence, cynicism, racial tension, class conflict and inferior schools where – no matter where buses dropped off students – the ultimate destination for too many kids was a dead end when it came to a great education and a better life.

Those years, Judge Garrity’s ruling, blood in the streets, two campaigns against Timilty, the increasing self-imposed isolation within the Parkman House, exhausted White but he never surrendered to bitterness.

No mayor of Boston before or since has had to deal with the tumult, the division, the demands of a federal court, the need for the city to grow or die, the ingrained cynicism and the perpetual parochialism that has been as much a part of our lives around here as air. Kevin White did it, with more wins than losses.

If you are new to town or if you have never left, look around this morning as you drive to work, go to lunch, walk the dog, wait at a bus stop, emerge from Park Street Under, run along the Charles. There is no need to read any obituary of Kevin H. White. You are looking at it. You are part of it. It’s called Boston in the 21st Century.

Deadline Artists: America’s Greatest Newspaper Columns

Edited by John Avlon, Jesse Angelo & Errol Louis

At a time of great transition in the news media, Deadline Artists celebrates the relevance of the newspaper column through the simple power of excellent writing. It is an inspiration for a new generation of writers—whether their medium is print or digital-looking to learn from the best of their predecessors.

This new book features two of Mike’s columns from The Boston Globe. The book says, “Barnicle is to Boston what Royko was to Chicago and Breslin is to New York—an authentic voice who comes to symbolize a great city. Almost a generation younger than Breslin & Co., Barnicle also serves as the keeper of the flame of the reported column. A speechwriter after college, Barnicle’s column with The Boston Globe ran from 1973 to 1998. He has subsequently written for the New York Daily News and the Boston Herald, logging an estimated four thousand columns in the process. He is also a frequent guest on MSNBC’s Morning Joe as well as a featured interview in Ken Burns’s Baseball: The Tenth Inning documentary.”

Read the columns here (you can buy the book by clicking here)

“Steak Tips to Die For” – Boston Globe – November 7, 1995

Those who think red meat might be bad for you have a pretty good argument this morning in the form of five dead guys killed yesterday at the 99 Restaurant in Charlestown. It appears that that two late Luisis, Bobby, the father, and Roman, his son, along with their three pals, sure did love it because there was so much beef spread out in front of the five victims that their table-top resembled a cattle drive.

“All that was missing was the marinara,” a detective was saying yesterday. “If they had linguini and marinara it would have been like that scene in The Godfather where Michael Corleone shoots the Mafia guy and the cop. But it was steak tips.”

Prior to stopping for a quick bite, Roman Luisi was on kind of a roll. According to police, he recently beat a double-murder charge in California. Where else?

But that was then and this is now. And Sunday night, he got in a fight in the North End. Supposedly, one of those he fought with was Damian Clemente, 20 years old and built like a steamer trunk. Clemente, quite capable of holding a grudge, is reliably reported to have sat on Luisi.

Plus, it is now alleged that at lunch yesterday, young Clemente, along with Vincent Perez, 27, walked into the crowded restaurant and began firing at five guys in between salads and entrée. The 99 is a popular establishment located at the edge of Charlestown, a section of the city often pointed to as a place where nearly everyone acts like Marcel Marceau after murders take place in plain view of hundreds.

Therefore, most locals were quick to point out that all allegedly involved in the shooting—the five slumped on the floor as well as the two morons quickly captured outside—were from across the bridge. Both the alleged shooters and the five victims hung out in the North End.

However, yesterday, it appears, everyone was playing an away game. For those who still think “The Mob” is an example of a talented organization capable of skillfully executing its game plan, there can be only deep disappointment in the aftermath of such horrendous, noisy and public violence.

It took, oh, about 45 seconds for authorities to track down Clemente and Perez. Clemente is of such proportions that his foot speed is minimal. And it is thought that his partner Perez’s thinking capacity is even slower than Clemente’s feet.

Two Everett policeman out of uniform—Bob Hall and Paul Durant—were having lunch a few feet away from where both Luisis and the others were having the last supper. The two cops have less than five years’ experience combined but both came up huge.

“They didn’t try anything crazy inside. They didn’t panic,” another detective pointed out last night. “They followed the two shooters out the door, put them down and held them there. They were unbelievably level-headed, even when two Boston cops arrived and had their guns drawn on the Everett cops because they didn’t know who they were, both guys stayed cool and identified themselves. And they are going to make two truly outstanding witnesses.”

The two Boston policemen who arrived in the parking lot where Clemente and Perez were prone on the asphalt were Tom Hennessey and Stephen Green. They were working a paid detail nearby which, all things being equal, immediately led one official to cast the event in its proper, parochial perspective: “This ought to put an end to the argument to do away with paid details,” he said. “Hey, ask yourself this question: You think a flagman could have arrested these guys?”

The entire event—perhaps four minutes in duration, involving at least 13 shots, five victims and two suspects caught—is a bitter example of how downsizing has affected even organized crime. For several years, the federal government has enforced mandatory retirement rules—called jail—on several top local mob executives.

What’s left are clowns who arrive for a great matinee murder in a beat-up blue Cadillac and a white Chrysler that look like they are used for Bumper-Car. The shooters then proceed to leave a restaurant filled with the smell of cordite and about 37 people capable of picking them out of a lineup.

“Part of it was kind of like in the movies, but part of it wasn’t,” an eyewitness said last night. “The shooting part was like you see in a movie but the fat guy almost slipped and fell when he was getting away. That part you don’t see in a movie. But what a mess that table was.”

“We have a lot of evidence, witnesses and even a couple weapons,” a detective pointed out last evening. “But the way things are going in this country it would not surprise me if the defense argues that they guys were killed by cholesterol.”

“New Land, Sad Story” – Boston Globe – November 23, 1995

Three Cadillac hearses were parked on Hastings Street outside Calvary Baptist Church in Lowell Tuesday morning as an old town wrestled with new grief. Inside, the caskets had been placed together by the altar while the mother of the dead boys, a Cambodian woman named Chhong Yim, wept so much it seemed she cried for a whole city.

The funeral occurred two days before the best of American holidays and revolved around a people, many of whom have felt on occasion that God is symbolized by stars, stripes and the freedom to walk without fear. But a bitter truth was being buried here as well because now every Cambodian man, woman and child knows that despite fleeing the Khmer Rouge and soldiers who killed on whim, nobody can run forever from a plague that is as much a bitter part of this young country as white meat and cranberry sauce.

The dead children were Visal Men, 15, along with his two brothers Virak, 14, and Sovanna, 9, born in the U.S.A. They were shot and stabbed last week when the mother’s friend, Vuthy Seng, allegedly became enraged at being spurned by Chhong Yim, who chose her children over Seng.

There sure are enough sad stories to go around on any given day. However, there aren’t many to equal the slow demise of a proud, gentle culture—Cambodian—as it is bastardized by the clutter and chaos we not only allow to occur but willingly accept as a cost of democracy.

The three boys died slowly; first one, then the other in a hospital and, finally, the third a few days after Seng supposedly had charged into the apartment with a gun and a machete. He shot and hacked all three children along with their sister, Sathy Men, who is 13 and stood bewildered beside her howling mother, the two of them survivors of a horror so deep their lives are forever maligned.

At 10:45, as the funeral was set to begin, two cops on motorcycles came up Hastings ahead of a bus filled with children from Butler Middle School. The boys and girls walked in silence into the chapel to pray for the dead who have left a firm imprint on their adopted hometown.

The crowd of mourners was thrilling in its diversity. There were policemen, firefighters, teachers and shopkeepers. The young knelt shoulder-to-shoulder with the old. There were Catholic nuns and Buddhist priests. There were friends of the family as well as total strangers summoned only by tragedy.

A little after 11 a.m., Hak Sen, who drove from Rhode Island, parked his car by the post office and headed toward Calvary Baptist Church.

“I am late. I got lost,” Hak Sen said.

“Are you a friend of the family?” he was asked.

“No,” he replied. “I do not know them. I come out of respect and sadness. We all make a terrible journey to come here to America and this is very, very bad.”

Hak Sen said he and his family were from Battambang Province, along the Thai-Cambodian border. He said that he served in the army before Pol Pot took over his country and that he and his family were forced to flee but not all made it to the refugee camps.

“I am lucky man,” Hak Sen pointed out. “I survive. My wife, she survive and two of our children, they survive.”

“Did you lose any children?” he was asked.

“Yes,” he said. “I lost three boys, just like this woman. Three boys and our daughter. They all dead. The malaria killed them in the jungle. There was not enough food and no water and they were young and could not fight the disease and they died. They all dead. My mother and father too.”

The innocent children inside the church as well as the big-hearted citizens of Lowell along with the majority of people who will buy a paper or carve a turkey today simply have no idea of the epic, tragic struggle of the Cambodians. They left a country where they were killed for owning a ballpoint pen or wearing a pair of eyeglasses to arrive in this country where, each day, we become more and more narcoticized by the scale of violence around us.

At the conclusion of the service, Lowell detectives Mike Durkin, John Boutselis and Phil Conroy helped carry the caskets to the hearses. The procession wound slowly through city streets, pausing for a few seconds outside the Butler School, where pupils lined both sides of the road like grieving sentries as the entourage entered Westlawn Cemetery.

“This is as sad as it gets,” said Roger LaPointe, a cemetery worker. “We cut the first two graves the end of last week but the funeral director told us we better hold on. When the third boy died, we had to cut it some more. It’s an awful thing. That hole just kept getting bigger.”

With husband Bob, Myra Kraft attended many fund-raisers, smiling and greeting donors. (1997 File/The Boston Globe) |

She was the conscience and soul of the Patriots, a woman who came to football reluctantly, through marriage, then used the currency of football fame to enhance her lifelong missions of fund-raising and philanthropy.

“Without Myra Kraft, it’s quite possible we’d be going to Hartford to watch the Patriots,’’ former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle said yesterday after it was announced that Myra succumbed to cancer at the age of 68. “Obviously, Bob Kraft has deeps roots in this area, but Myra was so much a part of this community – the larger community beyond the sports world – she was never going to allow her husband to leave.’’

We all knew Myra was failing in recent years, but she never wanted it to be about herself. Through the decades, thousands of patients were treated at the Kraft Family Blood Donor Center at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, but when Myra got cancer there was no announcement; instead, the Krafts announced a $20 million gift to Partners HealthCare to create the Kraft Family National Center for Leadership and Training in Community Health.

It was always that way. You’d go to a fund-raiser and Myra would be standing off to the side with Bob, smiling, greeting donors, and gently pushing the cause of the Greater Good. They were married for 48 years and had four sons who learned from their mom that more is expected of those to whom more is given.

It’s fashionable to enlarge the deeds of the dead and make them greater than they were in real life. This would be impossible with Myra Kraft. She was the real deal. Myra Hiatt Kraft was a Worcester girl, a child of privilege, and she spent her life giving back to her community.

Not a sports fan at heart, Myra was a quick study when Bob bought the team in 1994. Sitting next to Bob and eldest son Jonathan, she learned what she needed to know about football. When something wasn’t right, she spoke up. Myra disapproved when the Patriots drafted sex offender Christian Peter in 1996. Peter was quickly cut. She objected publicly when Bill Parcells referred to Terry Glenn as “she.’’ Like Parcells and Pete Carroll before him, Bill Belichick operated with the knowledge that Myra was watching. Keep the bad boys away from Foxborough. Don’t sell your soul in the pursuit of championships.

The base of Myra’s philanthropic works was the Robert K. and Myra H. Kraft Family Foundation. The Boys & Girls Clubs of Boston were a particular passion. Among its other missions, the Kraft Foundation endowed chairs and built buildings at Brandeis, Columbia, Harvard, BC, and Holy Cross.

BC and HC are Jesuit institutions. Myra Kraft was Jewish and worked tirelessly for Jewish and Israeli charities, but that didn’t stop her from helping local Catholic colleges.

“She was the daughter of Jack [Jacob] and Frances Hiatt,’’ Father John Brooks, the former president of Holy Cross, recalled. “Jack was a great benefactor of Holy Cross. He was on our board and was a very important person to the city of Worcester. I was a regular attendee of the annual Passover dinner at the Hiatt home when Myra was still living in Worcester. What struck me about Myra was that she was very proud and was a wonderful mother to her four boys.’’

During the 2010 season, Myra steered the New England Patriots Charitable Foundation toward early detection of cancer. Partnering with three local hospitals, the Krafts and the Patriots promoted the “Kick Cancer’’ campaign, never mentioning Myra’s struggle with the disease.

Anne Finucane, Bank of America’s Northeast president, held a large Cure For Epilepsy dinner at the Museum of Fine Arts last October and recalled, “Myra showed up at our event even though she was battling her illness and they were in the middle of their season. That’s the way she was. She could come and see you and make a pitch on behalf of an organization. There are people who just lend their name and then there are people who take a leadership role to advance an issue. She was a pretty good inspiration for anyone in this city.’’

Just as it’s hard to imagine the Patriots without Bob Kraft, it’s impossible to imagine Bob without Myra. After every game, home or away, win or lose, Myra was at Bob’s side, waiting at the end of the tunnel outside the Patriots locker room.

We miss her already.

Dan Shaughnessy is a Globe columnist.

Globe Columnist

July 20, 2011

Next time you feel like ripping Terry Francona, try to remember that the man has a lot on his mind. The manager’s son, Nick Francona, a former pitcher at the University of Pennsylvania, is a lieutenant in the United States Marine Corps, serving a six-month tour, leading a rifle platoon in Afghanistan. Twenty-six-year-old Nick is one of the more impressive young men you’ll ever meet. In a terrific piece for Grantland.com, Mike Barnicle asked Terry Francona how’s he doing as the dad of one of our soldiers at war. “I’m doing awful,’’ answered the manager. “My wife’s doing worse. I think about it all the time. Worry about it all the time. Hard not to. Try and stay away from the news about it. Try not to watch TV when stories about it are on, but it’s there, you know? It’s always there.’’

Two Interviews. Hard questions. Figuring out the partnership of Terry Francona and Theo Epstein, one of the most successful collaborations in baseball.

He is wearing white uniform pants, a red hot-top and black spike-less athletic shoes, a Red Sox cap on his hairless head. And he is staring at a cluster of numbers on the screen of a laptop. The numbers run alongside the names of those players who are in the starting lineup of the Baltimore Orioles, the Friday night game about four hours away. The numbers are mathematical guidelines to the recent baseball past: What Baltimore players did against Red Sox pitchers. Where players are most likely to hit the ball if they connect with a curve, a slider, or a cut fastball.

“Can’t call ’em stat-geek stuff,” Tito Francona volunteers. “That’s disrespectful. There’s a lot of good information here, matchups, stuff like that. People work hard at this.

“I used to do these by hand,” he says. “Did it before all this math stuff and computers got so big. Did it without knowing it. When I managed the Phillies. Did ’em all by hand then. Would sit down with a pencil and a piece of paper and go through opposing lineups. Took forever. Now it’s all on these things, computers.

“And I suck at computers,” he is saying. “I’m a one-finger guy with them. I can get around on a computer OK using one finger but it’s not my favorite thing.”

“How you doing otherwise?” he is asked.

“Exhausted,” he replies.

“How’s Nick doing?”

“He’s OK,” said the Red Sox skipper, now in his eighth summer of employment with a club that dominates daily discussion in New England. “Guys in his squad in front of him on patrol got hit the other day. Tough day for him. Good thing though, he loves what he’s doing.”

The father now talking about the son: 26-year-old Lt. Nick Francona, United States Marine Corps, halfway through a six-month, one-day tour leading a rifle platoon in a long war that has forever ravaged a country locked somewhere in centuries past, Afghanistan.

“You OK?”

“Awful, ” the manager says. “I’m doing awful. My wife’s doing worse. I think about it all the time. Worry about him all the time. Hard not to. Try and stay away from the news about it. Try not to watch TV when stories about it are on, but it’s there, you know? It’s always there.”

The phone on his desk rings and Francona reaches to answer with his left hand, the right-hand index finger slowly scrolling through the Orioles roster on his laptop, his eyes narrowing behind glasses, looking, always looking for an edge.

“Yeah Theo, what’s up?” he says, pausing to listen to the guy on the line, Theo Epstein, the 37-year-old general manager.

“Yeah, I spoke to Buck Showalter about that … OK … Talk to you later.”

“Theo,” Francona says, hanging up, a smile creasing his weary face. “How do we get along? We got through eight years here together. We haven’t killed each other. I’d say we get along pretty good.”

The Major League Baseball season runs from early February, across spring, through summer, and concludes for most players and teams just as Columbus Day approaches. The season, longest of all the majors and quite exhausting, is a bit like dating a nymphomaniac; it demands daily performance. And in Boston the expectation is always to play toward Halloween.

In some aspects the game has changed irrevocably since a young Tito Francona, his father’s first baseman’s mitt on his hand, ran to sandlots in the small Pennsylvania town where his family lived. Managers today are provided tools to compete that were simply not available 20, even 10 years ago. They have access to a Niagara of information sometimes spoon-fed by a generation of front-office young people who have rarely played actual games.

“People, some writers I guess, get that wrong you know,” Tito Francona points out. “Theo and the guys working for him, they’re not in here six times a day with stats telling us what to do. We get stuff before a series begins and it’s valuable. I study it. I do.

“But it’s about more than numbers,” he says. “I remember a few years ago, we’re playing the Yankees on national TV and one of the kids in baseball ops — he’s not here now — says to me about five hours before the game, ‘You got Mike Lowell in the lineup?’ And I say, ‘Yeah.’ And he says he doesn’t do well in the matchup with Chien-Ming Wang, who was pitching for the Yankees.

“I say to the kid, ‘So you don’t want me to play him?’ And he says, ‘Yeah’ and I tell him, ‘OK. Look over there. There’s Mikey Lowell’s locker. He’s over there. You go tell Mikey Lowell he’s not playing in a national TV game against our biggest rival ’cause your fucking numbers tell us not to play him. See what kind of reaction you get from him and then come back and tell me.’ Course Mikey Lowell played that game.

“That doesn’t happen a lot, though. It works pretty well, the numbers stuff and us down here.”

“What are the biggest differences between you and Theo?” Francona is asked.

“There aren’t a whole lot,” he answers. “We talk every day. It’s good. We’re not yelling ‘Shut the fuck up’ at each other either. He knows I value the input I get from him and the guys in baseball ops, but he knows my world down here in the clubhouse is different from theirs.

“I get it. He knows I get it. And he knows getting a player in winter is different from getting a guy ready in the seventh inning. In uniform you’re looking at today. Right now.”

Two different worlds. Francona and Epstein. They are characters out of a kind of baseball version of Upstairs-Downstairs the old PBS series about class and expectation. One is Ivy League. The other is Summer League. One grew up dreaming of baseball. The other played it, raised in a house with a father who made a living at it in the major leagues.

Terry Francona is 52 years old, a baseball lifer from New Brighton, Penn., where the median annual family income today is roughly $31,000. The town is 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, and it is a place where men worked factory jobs and women knew how to stretch every grocery dollar, day to day, week to week. He went to high school there, attended the University of Arizona, was a 1980 first-round draft choice by the Montreal Expos.

Theo Epstein, 37, grew up in Brookline, Mass., median annual family income, $120,000, in the shadow of Fenway Park. He went to Yale, was sports editor of the Yale Daily News, got a job as a summer intern with the Orioles, parlayed his energy and his instincts into a front office position with the San Diego Padres, came home to Boston when John Henry, Tom Werner, and Larry Lucchino purchased the Red Sox in 2001. Took over as general manager in 2003, a lifelong dream in his back pocket at age 29.

The other day Epstein was sitting in a conference room located in the bowels of the ballpark, in a space that used to be part of an old bowling alley before it and much of the rest of Fenway was renovated and rebuilt under the watchful eye of Lucchino and ballpark architect Janet Marie Smith. He is a confident, disciplined, self-contained young guy, cautious with language and body movement, always alert that in the crazed media atmosphere that surrounds the Red Sox, one dropped syllable or the wrong adjective could put thousands of talk-show callers into crisis mode. In addition to statistics, the semantics of baseball have changed, too, young front-office people far less reliant on one of the locker-room staples of the game: The F-Bomb.

“What do you think Tito said about you?” I ask Epstein.

“Ahh,” he says, “he probably said we worked really well together. That we understand each other and respect the differences between our two jobs, and that he knows I have his back.

On the walls of the conference room were several white-boards filled with names of high school and college players just drafted, along with others to be looked at in fall ball leagues. The future hanging right there. The immediate, game no. 89 on the march to 162, four hours away.

“Actually we’re like an old married couple,” Epstein adds. “I can usually tell from his facial expression what kind of mood he’s in. And there is an element of ‘his’ world versus ‘my’ world in the relationship, but we’ve learned to pick our battles, and as well as I know him he knows me too.

“Communication is different in the clubhouse than it is in a boardroom. The heartbeat that exists in the clubhouse … you don’t find that same type of heartbeat in the front office. There is a cloak of intensity in the clubhouse that doesn’t exist here,” the general manager points out. “There is a little more objectivity here in this office. We see the game at 10,000 feet. Tito sees it 50 feet away. Tito is looking at tonight’s game and those of us in baseball ops, a lot of the time, are looking at the next five years.

“His job is clear: Win tonight’s game. That’s his focus. Ours is that, as well, but the focus is also on the years ahead. That’s the inherent conflict between the two jobs, his and mine. It’s the subjective versus the objective.”

“What did you want to know from him when he interviewed for the job?” Theo Epstein is asked.

“That’s interesting,” he replies. “The big thing was what kind of relationship would exist? Would both of us be willing to say anything to the other without worrying about hurting feelings?”

“Right before I interviewed for the job with Theo, I called Mark Shapiro of the Indians. He’s one of my best friends in baseball and I asked him what I should do,” Tito Francona was saying earlier. “He gave me good advice I still use today. Mark told me, ‘Just don’t try and bullshit him.'”

“It’s become like a family relationship,” Epstein says. “You can’t bury things. We get them out in the open. I recognize the limitations of my view and my background but the two of us work well together.”

Epstein had just returned from lunch with his father, Leslie Epstein, who retired as head of the creative writing department at Boston University. The day before, a 39-year-old Texas firefighter sitting at a Rangers game alongside his 6-year-old son had died after falling out of the stands in pursuit of a foul ball tossed toward him as a generous gesture by Texas outfielder Josh Hamilton.

A dad’s dying young, at a ballpark, his little boy bearing eternal witness, clearly touched Epstein. He is sometimes labeled as cold and impersonal in his approach to whom he wants on or off his roster and what his club’s needs are, but what took place in Texas clearly triggered a reality he knows well: He is a young man living a dream.

“When I heard about that I wanted to have lunch with my dad,” Theo Epstein says. “What an awful story.”

In the manager’s office, Francona, his son Nick constantly on his mind, was attempting to lose himself in the landscape of a baseball game about to be played with the Baltimore Orioles.

“Theo knows,” Francona says with a slight laugh. “He knows he’s already looking at next year’s draft and he knows I’m down here looking at the seventh inning tonight. That’s the game.”

Mike Barnicle is an award-winning journalist. This is his first article for Grantland.

Mar. 1, 2011

BOSTON — The Harvard community — and people the world over — is mourning the death of Reverend Peter Gomes, the man who ran the university’s Memorial Church for over forty years.

Gomes died Monday night because of complications from a stroke he had in December. He was 68.

|

| The Reverend Peter Gomes died Monday at the age of 68, after a more-than 40-year ministry at Harvard University. |

Gomes’ longtime friend, writer and columnist Mike Barnicle, met Gomes because the two would regularly spend early mornings at the same restaurant. “He was an education to sit with, next to, to listen to, a sheer education. Not just in terms of his moral values but his view on the world,” Barnicle told WGBH’s Emily Rooney on Tuesday.

A black, openly gay minister, Gomes was a decided rarity. He came out about his sexuality in 1991.

He was also politically conservative for most of his career, although he changed his political affiliation to Democrat to vote for Gov. Deval Patrick in 2006.

Barnicle said Gomes learned from his own experience being different, and set out to help others with theirs.

“He was was an expert at honing in on the demonization of people,” Barnicle said. “He could see people and institutions being demonized well before it would become apparent tthat they were being demonized.”

That, Barnicle said, gave Gomes a sense of fairness that underguarded his political and religious beliefs.

“It’s not fair to go after people because of who they are, or because of their sexual orientation, or because of their color, or because of their income, or because of their zip code. That’s who he was, he was an expert in what’s fair,” Barnicle said.

Gomes was known for his soaring, intricate speaking style. “I like playing with words and structure,” he said once, “Marching up to an idea, saluting, backing off, making a feint and then turning around.”

“His sermons were actually high theater in my mind,” Barnicle remembered.

Gomes did not leave behind a memoir; He said he’d start work on it when he retired, at 70. It’s a shame, Barnicle said. “We need more of him than just a memoir, we need people like him every day.”

Gomes reflected on his life’s work — and his death — on Charlie Rose’s talk show in 2007.

I even have the tombstone the verse on my stone is to be from 2 Timothy. “Study to show thyself approved unto God a workman who needeth not to be ashamed, rightly dividing the word of truth.” That’s what I try to do, that’s what I want people to thnk of me after I’m gone. When I was young, we all had to memorize vast quantities of scripture and I remember that passage from Timothy I thought, ‘Hey that’s not a bad life’s work.’ And in a way I’ve tried to live into it. So my epitaph is not going to be new to me, it’s the path I have followed in my ministry and my life.

Mike Barnicle talks about the baseball gloves he’s had since 1954. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

Mark Feeney from the Boston Globe says, “Mike Barnicle, who toiled for many years at this newspaper, serves as representative of Red Sox Nation. One of his great strengths on both page and screen has always been what a potent and vivid presence he has.”

Mike Barnicle talks about the Red Sox loss of 2003 to the Yankees and how it impacted his son, Tim. “The Tenth Inning,” is a two-part, four-hour documentary film directed by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick that premieres this week, September 28 & 29th at 8pm ET on PBS. A new chapter in Burns’s landmark 1994 series, “Baseball,” “The Tenth Inning” tells the tumultuous story of the national pastime from the 1990s to the present day.

David Barron of the Houston Chronicle calls Barnicle’s contribution to the film “perhaps the most valuable addition… (Barnicle) provokes simultaneous laughter and tears on the burden of passing his love of the Red Sox to a second generation….”

“The tale of the Sox bookend years of failure and triumph are given a personal connective thread by former Globe columnist Mike Barnicle, who frames the story through the eyes of his children and his late mother, who, Barnicle recalls, used to sit on a porch in Fitchburg, Mass., her nylons rolled down, listening to the Sox on the radio and keeping score on a sheet of paper.” — Gordon Edes for ESPN.com

Watch here: https://video.pbs.org/video/1596452376/#

Sunday, Jan. 17, 2010

In Massachusetts, Scott Brown Rides a Political Perfect Storm

By MIKE BARNICLE

Scott Brown, wearing a dark suit, blue shirt and red stripe tie in the mild winter air, stood a few yards in front of a statue of Paul Revere and directly across the street from St. Stephen’s Church, where Rose Kennedy’s funeral Mass was celebrated in 1995, telling about 200 gleeful voters that they had a chance to rearrange a political universe. The crowd spilled across the sidewalk onto the narrow street that cuts through the heart of the city’s North End, the local cannoli capital, located in Ward 3 that Barack Obama carried 2 to 1 just 15 months ago.

” ‘Scuse me,” Joanne Prevost said to a man who had two “Scott Brown for Senate” signs tucked under his left arm. “Can I have one of those signs? I’ll put it in my window. My office is right there.”

She turned and pointed across the street to a storefront with the words ‘Anzalone Realty’ stenciled on window. “Everybody will see it.” (See the top 10 political defections.)

Read the rest of the article at: https://www.time.com/time/politics/article/0,8599,1954366,00.html?xid=rss-topstories

Mike Barnicle is a veteran print and broadcast journalist recognized for his street-smart, straightforward style honed over nearly four decades in the field. The Massachusetts native has written 4,000-plus columns collectively for The Boston Globe, Boston Herald and the New York Daily News, and continues to champion the struggles and triumphs of the every man by giving voice to the essential stories of today on television, radio, and in print.